Reviews and Recollections - From 1975 to 1978.

Looking back at them now, the large number of reviews the 600 range was given in magazines actually turns out to be an interesting way to document changes that were taking place in the 1970s and into the 1980s. In narrow terms, in the first half of the 1970s Armstrong was one of the main UK makers of quality Hi-Fi equipment and the change was dramatic – in less than a decade they’d ceased manufacturing entirely! However the way this happened, and the reasons behind it can now be used to shed light on the problems that UK manufacturing in general – and Hi-Fi in particular – faced.

If you have already read the Early Silicon Era page. and compared the reviews discussed there you may already have noticed that they sometimes show conflicting results for some measurements. In part, this was because the 600 range electronics was often modified to produce small improvements. But it was also due to different reviewers performing measurements and deducing conclusions in different ways. Examples of the observer affecting the observed! This variability increased during the second half of the 1970s as the background and approach of reviewers and magazines altered. The Early Silicon Era page already outlines the main features and performance of the 600 range units. Rather than duplicate that, here I will concentrate upon details in individual reviews that expose variations in their measured results and the views expressed. This provides a basis for examining the changes that were taking place. In essence, it provides evidence which can be used to ‘review the reviewers’!

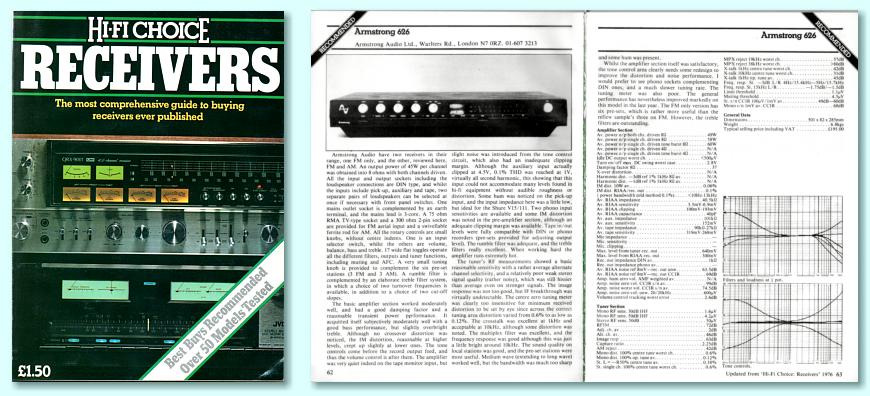

There were a series of Armstrong 600 series reviews in “Hi-Fi Choice” magazine during the second half of the 1970s. These issues were ‘pocketbook’ size (approx 147 x 198 mm) and many were undated. The absence of any cover-date was deliberate. Each issue published a number of reviews of the same type of unit. So one issue might be on amplifiers, the next on loudspeakers, the next on cassette decks, etc. By omitting a cover date, each issue could have a longer ‘shelf life’ in the newsagents, and one or more issues on different types of equipment could be on display at the same time. Unfortunately, the absence of cover dates can now make identifying the actual time of publication difficult!

Each issue essentially gave the reports as a ‘group review’. The individual examples were all subjected to a similar set of tests, and the results presented in a common format. In part this was because by the late 1970s Hi-Fi equipment had become one of the main ‘must have’ consumer items and there were a large number of competing models on sale. So the idea of these ‘group review comparisons’ was that someone wanting to buy, say, an amplifier, could get one issue and go though it. compare what was on offer on a ‘like-for-like’ basis to choose the one they preferred.

Behind the scenes, though, these group reviews began to serve another purpose. By this point the amount of expensive test equipment, skill, and reviewer’s time required to carry out an individual technical review had grown. However the amount a magazine could pay for a single review remained limited. So the challenge for the reviewers was – how to make this pay their wages and costs? One advantage of the group review was that each individual item review could often be reprinted in the next issue(s) on a given type of unit. Hence increasing the opportunities to bring in cash to cover the costs and make the whole process worth their effort! A good reviewer could still conscientiously produce reliable reviews. But there was also sometimes a pressure to “do ‘em quick and shovel ‘em in”. It may be significant that not all issues of ‘Hi Fi Choice’ of the period showed the name of the reviewers. This now also complicates assessing any differences between what reviews on the same model said.

Because of the absence of cover dates for the following issues of ‘Hi Fi Choice’ I’ve also shown what the cover of the relevant issues looked like. This should help anyone wanting to track a copy down and check its contents. The issue numbers I give are ones that Steve Harris (ex-editor of “Hi Fi News”) has assigned to the issues on the basis of his own research.

1976 Hi Fi Choice No 2 – 626 Review by Angus McKenzie

Angus McKenzie was one of the best technical reviewers of the period. In general he carried out measurements in a very meticulous way and his reviews were highly regarded. He also tended to be very critical and sought to uncover slightest departures from perfection. He began this review with the usual general description of the 600 units before adding some specific comments:

“The basic amplifier section worked pretty well, and had a good damping factor and a reasonable transient power performance. The half power response was a little limited, extending to about 13kHz, but not withstanding this the amplifier section acquitted itself subjectively very well with a good bass performance, but slightly over bright treble. Although no crossover distortion was noticed...”

{N.B. As printed this review said “Although no crosstalk over distortion...”. However this was corrected to the above when the review was essentially republished in 1977.]

It is worth noting the comment here regarding the half-power bandwidth because this seems to be a measurement where reviewers measured and reported values that varied to a surprising extent. An earlier review had said the half-power bandwidth extended to 50kHz. And as we shall see later on, another Hi Fi Choice review gave a dramatically different value! The comment about “slightly over bright treble” is curious because the 600 range units had tone controls. We can’t now know, but it may well be that a slight tweak of the ‘treble’ control would have corrected this impression. The review indicates that this “over bright treble” wasn’t due to distortion. He went on to say:

“The tone controls come before the record output feed, and thus the volume control is after them. The amplifier was very quiet indeed on the tape monitor input, but slight noise was introduced from the tone control circuit, which also had an inadequate clipping margin. Although the auxiliary input actually clipped at 4·5V, 0·1% THD was reached at 1V”

To put these comments into context it is worth noting that the actual rated input sensitivity was 100 mV. Hence a 1V input nominally corresponded to 20dB of overload for the design. At the time it seems likely that many of the home audio signal sources which might be used – tuners, tape decks, etc – either didn’t output levels as high as 1 Volt, or would have generated more than 0·1% distortion themselves at such levels. Overall, though, the review was favourable although it did conclude with:

“In general we feel that the receiver will clearly suit many fairly discriminating users, despite its few failings. Local lower frequency transmissions picked up on the mains or loudspeaker leads will cause severe trouble unless you insist on a specially suppressed model. Your dealer will have to send back a receiver for this modification.”

Some versions of the 600 series amplifier were more prone to RF pickup from the leads in this way. But in practice most users, and other reviewers didn’t comment on this or seem to have encountered it.

1977 Hi Fi Choice No 6 – 621 Review by Hugh Ford

I have some vivid recollections related to this particular review for reasons which should become clear as I discuss what it said! The review did make a number of positive comments and describes some features which other reviews overlooked. For example, it said:

“Unlike most loudness controls, the one on this amplifier introduces 20dB attenuation at 1kHz whilst boosting the bass and treble, rather than relying upon the setting of the volume control — thus, the range of the volume control is increased and it must be mentioned that neither the loudness control nor any other controls introduced significant changes in balance between the amplifier channels.”

A “loudness” control was a feature which some users of the period expected or found handy. It tailored the frequency response so that the low bass and high treble became louder than the midrange. Some people had argued that this gave a better sound when replaying music at a level lower than the original sounds when they were recorded. However this idea has now gone the way of ‘tone controls’ in general.

The review went on to say:

“There is also a disc input sensitivity control which gives a sensitivity of either 2·9mV or 5·8mV, and this is decidedly necessary in view of the rather small overload margin on the disc inputs.”

The view expressed about the “rather small overload margin” is a curious one for the following reasons: The measured results tabulated in the review itself reported that the disc (RIAA) input overloaded at 90 mV when set to 2·9mV (nominally 3mV) sensitivity. This corresponds to an overload margin of just under 30dB.

Now in practice I have recorded and measured the output from hundreds of Vinyl LPs over the years. Most recently, using high resolution equipment with a sample-accurate peak level reading. It is unusual for an LP to have any peaks reaching as high as 18dB above the RIAA reference level. (Excepting loud ‘bangs’ due to nasty scratches!) Even allowing for someone using a cartridge whose sensitivity produces 5 mV for a 0dB(RIAA) level, this means it would be very rare for a musical peak to come within 10dB of being greater than the level the 621 could handle. In addition, most cartridges would either fail to track such high peaks, or would produce a highly distorted output anyway. What is, and was, true is that some other amplifiers provided larger overload margins. But it seems questionable if that actually mattered much in practice. Hence – as has often been the case with reviews – the comments here may have been made on the basis of comparing with some ideal rather than actually what works fine in real use.

The review continued with:

“So far as noise is concerned, this amplifier is quite good, particularly the noise at the output at lower volume settings.”

and:

“The subjective performance was generally good with no troubles in handling overloads. However, the high frequencies sometimes sounded a little muddled, probably as a result of the rather poor power bandwidth.”

The first point which stands out here is that the comment “the high frequencies sometimes sounded a little muddled” which seems to conflict with “...slightly over bright” in the earlier review by Angus McKenzie.

In use, the output impedance of a power amplifier can interact with the input impedance of the chosen loudspeakers in a way that can audibly affect the frequency response. This can mean that an amplifier sounds “bright” when used with one model of speakers, and “muddled” with another. The problem is that such comments may tell you more about the choice of loudspeakers than it does the amplifier! And when the amplifier has tone controls (as was the case for the 600 range) their precise adjustment could easily alter the result from being slightly “bright” to slightly “muddled”. So such comments in reviews may simply mean the reviewers used different speakers for their listening tests and/or didn’t ensure exactly the same tone control settings. Factors like these can easily explain why reviews may make conflicting comments about the ‘sound’ of audio equipment.

For much the same reasons, such comments may be worse than useless for readers of the reviews. Unless the reader know what speakers the reviewers used – and uses the same ones themself in a listening room with the same acoustics, etc – such comments may be a hopelessly misleading guide to what the reader would get using the same amplifier. This is a fundamental problem which afflicts many ‘subjective’ comments in reviews. In effect, the comments become ‘disinformation’ that makes it harder for them to find the best possible choice for themself.

We then have the comment about “...rather poor power bandwidth”.

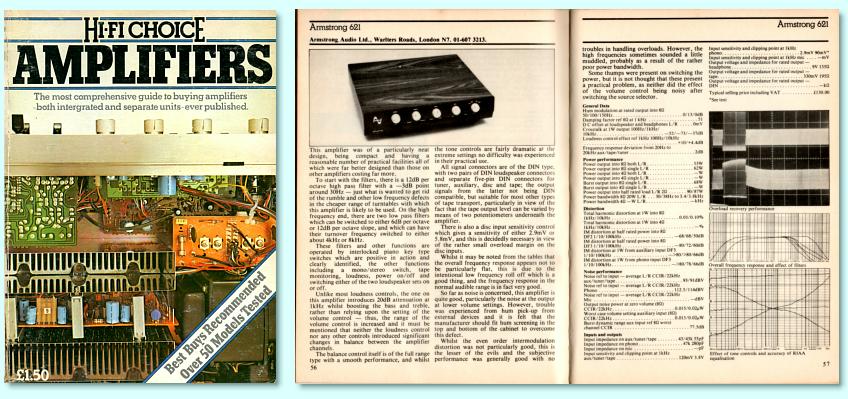

I have reproduced, below, the section of the measured results as printed in the review.

The measured results for the power output are fine. They show that by this point the 600 range’s power amplifier section had improved to the point of delivering over 50 Watts per channel. (Although the published spec remained lower.) However the measured results for the “Power Bandwidth 8 Ohm 20W” are clearly wildly different to the results produced in every other review. When I and others at Armstrong saw this review we realised it was wrong, and could do unfair harm to the sales and reputation of the 600 range. Having a half power bandwidth that is as limited as 38 Hz to 3·4kHz would mean it was doubtful that the amplifier was suitable for hi-fi use. My own measurements, and that of others, gave far better values.

This issue of Hi Fi Choice does not name the reviewer. So we contacted the publishers, and then Alex Grant, Barrie Hope (both directors of Armstrong) and myself (at that time the electronic designer responsible for the amplifiers) went to see him. The reviewer was in fact Hugh Ford. Alex and Barrie were angry and annoyed because of the likely negative impact of what had been published. I was puzzled by how such a result could have been obtained and published.

We discussed with Hugh Ford how he had carried out the measurement. It immediately became clear to me that he had made an elementary slip. As an audio engineer I was baffled by how an experienced reviewer could make such a mistake, but I assume he was simply too rushed doing many reviews. It was a mistake that would only affect the results for some amplifiers. So it would have been easy for him to be lulled into assuming that his test method was OK when it was actually flawed. I will try to explain the nature of his error below, but if you’re not interested in the engineering and feel the next section is too technical, skip over it. Just bear in mind the lesson that this review was a classic case of a ‘rogue’ result being published, misleading the readers.

|

The curious case of the mysterious loss of power bandwidth...

In their simplest form, half-power bandwidth measurements attempt to proceed as follows. Firstly, you check how much output power an amplifier will produce at some convenient ‘middle’ sinewave frequency – say 1 kHz – with a appropriately low level of distortion. For the sake of example, we can assume the result of a test gave us 40 Watts for this value with a given amplifier. You then find out how high or low a sinewave frequency you can get the amplifier to output at 20 Watts (i.e. half the mid-frequency power) with similarly low levels of distortion. The precise results depend on details like what distortion level the tester chooses as the ‘target’ amount they will use. Hence with low-feedback designs from the 1970s or earlier it wasn’t unusual to find the results of such tests varied a bit from one review to another. But in this case something else was wrong. When Hugh Ford explained how he’d made his half power bandwidth measurements we realised his mistake. The cause was the way he had adjusted the amplifier and input signal generator to set the output to ‘half power’. He had started with the volume control wound fully clockwise (maximum gain) and adjusted the 621 to give 40 Watts out at a middling frequency. He had then wound the volume control down ‘half way’ – i.e. to the 12 o’clock position. He had been assuming this (roughly) halved the amplifier’s gain. i.e. it would give about 20 Watts. He then adjusted his signal generator to get the power output to be exactly 20W. He then changed the output frequency and level from his signal generator until he found the highest and lowest frequencies where an output of 20W had no more than his ‘target’ level of distortion. If you’re not an audio engineer or someone familiar with how the electronics in a hi-fi amplifier works, that seems fine. But it included a fundamental error. Winding down the volume control by half of its rotation does NOT halve the gain and reduce what would be 40 Watts output to 20 Watts output. The precise result will depend on the ‘law’ of the volume control used by the amplifier designer. This determines how the level alters as you operate the control. But in almost all domestic hi-fi amplifiers, rotating the control to ‘half way’ or ‘12 o’clock’ will reduce the output power down to more like one hundredth of the full-gain power than a half! Because of this, he was then winding up the signal level being input from his signal generator until it was a great deal larger than when he had measured the full power at middling frequency. Some amplifier designs feed the selected input signal directly to the volume control. (The main exception being inputs for playing LPs which require a specific type of pre-amplifier.) For these designs Hugh Ford’s mistake didn’t matter much. The excessively large input was reduced by the volume control again before it encountered any amplifier stages that might distort the signal. However some other amplifiers include a ‘buffer’ amplifier stage before the volume control. In the case of the 600 range this was a feature of the design. The amplification stage before the volume control also provided the tone controls and filters. The reason for this was that it allowed the tone controls and filters to be used to modify what was output from the ‘tape out’ socket. This particular feature was welcomed by many users. The most well known example at the time was the BBC Radio 2 presenter, Alan Dell. He used to pre-record his programs onto tape for broadcast. He wanted the best possible sound to be broadcast and used the 600’s tone controls and filters to tweak the results when he was including a song from an LP that was less-than-perfect. Alas, because of the above mistake, when Hugh Ford did his tests he was significantly overloading this amplifier stage before the volume control. In principle the half power bandwidth check was meant mainly to assess the capability of the power amplifier section. But the way the test was being done was actually overloading the pre-amplifier section. As soon as I realised what he had been doing I pointed this out. He agreed that he had made a mistake, and apologised. He said that it would be corrected in any later re-issue of the review. Alas, by that time the existing issue had been printed and sold to readers. Who then had read this misleading result. This episode is perhaps relevant as an precursor of how things were changing in hi-fi reviewing during the 1970s. My own opinion on this is fairly simple. People – even well qualified and experienced ones – make mistakes. To err is human. But the real failing here was the failure to check with the makers and give them a chance to detect and point out any rogue results before they were published. Problem like this cropped up again, later, in other guises. Now back to the main plot... |

1977 Hi Fi Choice No 7 – 626 Review by Angus Mckenzie.

Note that – although the cover of this issue doesn’t name the reviewer – this review is essentially a reprint of one in the 1976 “Receivers” issue discussed previously. The wording is almost identical. Given that, I’ll pass over it here but show the cover above for identification purposes.

1978 March “Audio” (USA) – 625 Receiver (Amp + FM tuner) Review by Leonard Feldman

N.B. I’ve only ever seen a faxed copy of the ‘galley’ proofs for this review! It was sent to Armstrong a few months before the actual review was published to give us a chance to comment on what it contained.

The review began with:

“The very good looking Armstrong 625 stereo FM receiver tested for this report is part of a family of products distributed in this country by Roth/Sindell, Inc., of Los Angeles.”

and went on to say:

“As is the case with so many good sounding British and European high fidelity products, the emphasis seems to be less on impressive printed specifications and more on listening quality and elegance of styling. What Japanese or American manufacturer would dare come up with an amplifier THD rating as high as 0·18 per cent in a receiver expected to sell for nearly $500 these days? And how many high-quality tuner sections would admit to roll-off of 3 dB at 15 kHz? Well. don’t let the seemingly ‘poor but honest’ published specs fool you. This line is "high end" all the way.”

The 625 retailed at the time in the United Kingdom for around £170. So the $500 price in the USA may well reflect the added costs of shipping to LA and the margins added in the USA.

Feldman then gave the usual general description of the 600 range units before adding some quite detailed information about the electronics:

“Fixed ceramic bandpass filters are used between stages of the IF section, and a CA3012 IC serves as the final amplifier-limiter of this section, driving a full Foster-Seeley discriminator FM detector circuit The stereo decoder section utilizes a CA3090 phase-lock-loop MPX IC with frequency lock accomplished by means of a single adjustable coil. Outputs are passed through a low-pass filter for suppression of sub-carrier products.”

“The two n-p-n power output transistors are powered from a single +82 volt supply. so that the audio take-off center point between the pair must be capacitor isolated. A 4700 microF coupling capacitor is used to isolate between this point and the speaker terminals. In terms of protection circuitry, the 625 has individual fuses in the voltage supply. lines feeding the output stages of each channel as well as a thermal cutout in the ordinary circuit of the power supply transformer. The power transformer, clearly visible in the internal view of the receiver, is toroidally wound. Circuit layout within the chassis was orderly and well executed.”

Later versions of the 600 range use a different Texas Instruments stereo decoder IC (SN75115N) along with an improved output filter made to suit by Toko. These provided a better performance from FM stereo. The ‘thermal cut-out’ was introduced when new safely laws came into force that limited the maximum temperature for any external part which could be touched. It was added to prevent the risk of the user burning their finger from touching a hot heatsink! Earlier versions of the 600 range power amp did not have a the thermal cut-out.

Amongst the measured results the review included:

“The power amplifier sections of the 625 delivered 47 watts per channel at mid-frequencies for rated harmonic distortion of 0·18 per cent. IM distortion measured 0·13 per cent for 35 watts of equivalent output per channel, both channels driven.”

“Damping factor using an 8-ohm reference was 53 at 1 kHz.”

“RIAA equalization was accurate to within 0·2 dB over the entire audio range, and signal to noise (measured for the more sensitive input setting) was 72 dB referred to actual input sensitivity and unweighted.”

Having considered the measurements Leonard Feldman then said:

“All of which brings us to a dilemma faced by many an audio product tester. If you have read this report carefully to this point, you may have concluded that the Armstrong 625 receiver is really nothing special. Indeed, competitive products selling for considerably less have more impressive "measured" specs and even a few control features (such as twin phono inputs, double tape-monitor circuits, etc.) that the 625 lacks. All these logical and rational observations hold up well until you start listening to the receiver. Reproduction in phono is absolutely superb. Given a decent outdoor antenna connection, FM reception is great, too. Dial calibration is very precise and, unlike other pre-set tuners and receivers that depend upon voltages applied to varactors for tuning, we detected absolutely no drift, regardless of whether we pushed the buttons for our six favourite pre-set stations or used the manual tuning mode (which is really nothing more than a precision potentiometer that picks off a varying dc voltage for application to those varactor diodes). Control operation is smooth and precise and, as claimed, there are no pops and clicks either at turn on or when switching from one program source to another.”

“According to a letter we received from Roth/Sindell, the U.S. distributors of the Armstrong line, the tuner section of this receiver (which is identical in the entire line) is used as a separate tuner for monitoring purposes by the BBC in Great Britain. Certainly, they could have chosen a tuner that "measures" better for that purpose - and so could you. But in terms of audible performance, we can fully understand the choice. The tuner does offer excellent FM reproduction when presented with signals of stations whose program practices are good.”

“As for why the receiver sounds so good but "measures" just average, if I knew the answer to that question, many, of the daily and weekly frustrations I experience in the course of testing equipment might be a thing of the past. For the moment, I can only judge by what I hear - and what I heard in the case of the Armstrong 625 was very good indeed.”

Comparing this review with others, we can see a fairly typical variation in the results from the measurements carried out. In terms of the ‘subjective’ comments it also shows just how much these can vary from one reviewer to another!

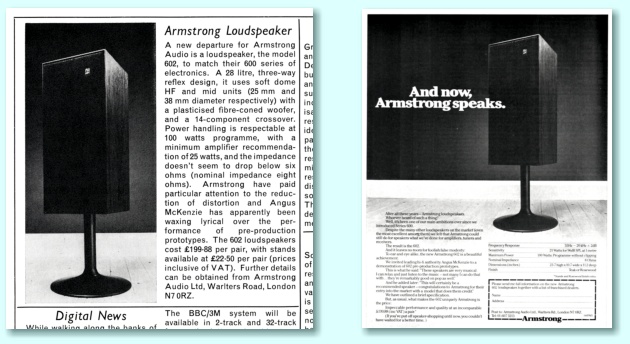

The 602 Loudspeakers

The 602 loudspeakers were launched and went on sale at the beginning of 1978. For some years before this one of the most common questions Armstrong was asked at audio shows was, “Do you have any matching speakers?” So it was decided to produce the 602.

The release was the subject of a ‘News’ item in the January 1987 issue of “Hi Fi News”. This was accompanied by a full page “Armstrong Speaks” advertisement in that magazine, and in the other main magazines, “Hi-Fi Answers”, “Popular Hi-Fi”, etc.

Angus McKenzie had been employed to act as a ‘consultant’ to test and comment on development pre-production versions of the 602. In part this was following a practice that had grown and become widespread during the 1970s. As a result it was possible to publish some of his comments in the news release and the advertisements. The adverts included the following quotes from what he had written about the 602:

“These speakers are very musical. I can relax and just listen to the music – not many I can do that with... they’re very good on pop as well. This will certainly be a recommended speaker – congratulations to Armstrong for their entry into the market with a model that does them credit.”

The adoption of the use of ‘hired gun’ consultants was a useful way for a maker to get an independent and educated cross-check to ensure their products were satisfactory before putting them on sale. However the practice came with some attendant risks, particularly if the same reviewers were subsequently also reviewing the same items for a magazine alongside competing products which they had not been paid to comment upon by the makers.

The key question it raised was, “How would magazine editors or readers be able to tell if a published reviews was affected by the reviwer having been paid by some of the makers involved? For example: It would perhaps be hard for a reviewer to raise problems or flaws in a magazine review that they’d missed in a pre-production examination. Their mind might also be pre-disposed to what they’d ‘expect’ to find. Whereas with a model they’d not encountered before they might be more focussed on searching for limitations or flaws. When combined with other changes in how reviewers and magazines behaved it – in principle at least – also opened the area to a risk of a conflict of interest. That reviewers who also operated as maker-paid consultants could perhaps earn more money if makers felt that not paying for such consultancy work increased the risk of errors or over-critical remarks appearing in a later magazine review.

In the case of the 602 Angus McKenzie’s name was published along with his comments, so at least magazine readers – and editors! – could know he had already been consulted and paid for his work. However this wasn’t alway so for other makers, models, or consultants/reviewers.

Again these risks one advantage was that pre-release consultancy would at least ensure the reviewer/consultant actually had a dialogue with the maker and any omissions or misunderstandings of the kind instanced by the 1977 ‘Hi Fi Choice’ review of the 612 could sorted out before any magazine review appeared. This topic became relevant again later on in the Armstrong story.

1978 March “Practical HiFi” – 602 Speakers as part of a ‘system’ Review by Philip Mount

I have not yet found any examples of a magazine review that simply examined the 602 speakers, although I imagine some were published. Up until the early 1970s most reviews of Hi-Fi units examined one specific model in detail. They also tended to be carried out by engineers who made exhaustive measured checks on the performance. However by the second half of the 1970s ‘system’ reviews were becoming quite common. These put together a hi-fi system from selected units. This could be useful if the items were well matched and worked happily together. But it could lead to problems if the reviewer attributed some aspect of performance to the wrong cause. And it made it harder for readers who already had a quite different system who wanted to change a single item to decide if the comments in the review would apply in their situation or not. These problems were often made worse due to a lack of measured objective results, displaced by ‘subjective opinions’ that might – or might not! – be relevant for the reader.

With the hindsight of almost 40 years this particular review now serves as an interesting example of what could happen. When considering the ‘system’ and the resulting comments, it may bring to mind the old comment that, ‘A camel is a horse put together by a committee!’...

The review spreads over 6 pages of the magazine, but less than two-thirds of a single page were devoted to the 602 speakers. The nature of the review is perhaps flagged by its title, “COMET gets the pioneer spirit”. It began with an explanatory box of text that said:

“Comet must be one of the best-known retailers in the country, specialising in hi-fl and all types of electrical goods. This is probably largely due to their 137 warehouses and shops which span the country. Indeed they now have more High Street shops than warehouses, which may come as something of a surprise. What many people don't realise is that each has a display area where their whole range of hi-fi equipment is on show. More important is their strong after-sales service facilities which are given top priority.”

This last comment, and some other comments in the review, give the strong impression that the system was selected and put together by Comet as a publicity scheme for Comet! Particularly because Armstrong at the time provided a highly regarded 48hour-turnround no-quibble repair service of their own! The boxed text continued with:

“Philip Mount's super system this month is based largely on Pioneer equipment. Their quartz-locked PLC-590 direct-drive turntable at £269.90 from Comet is married to the latest SME 3009 Mk III arm at £99.90. Cartridge is the new ADC ZLM Mk III costing £69.90 – a considerable saving. A Pioneer SA-9500 Mk II amplifier is priced by Comet at £304.90, and likewise the latest matching TX-9500 Mk II tuner, costing £249.90, provides radio signals. Final source is the Pioneer RT- 707 reel-to-reel tape machine at £347.90. Loudspeakers are the first from Armstrong – the 602 Monitors at £169.90 per pair. The mounting rack shown on the cover is an optional extra.”

And went on to point out the price difference between Comet and the full retail prices, strengthening the impression that the system components may have been chosen by Comet for their own reasons.

The Armstrong 602 section of the review began with:

“At the tail end of this large and expensive system sit a pair of Armstrong loudspeakers. Quite frankly I think that the person who compiled this system could have chosen something larger for they are hardly what most people would consider a true match for the other items. Price hovers around £170 which is reasonable viz-a-viz quality and size but is a rather small proportion of system cost, taking just the disc-playing chain. One normally expects as a rule of thumb to spend about 40 per cent of total budget on speakers in a disc chain but in this instance a figure of around 18%. per cent is achieved.”

This seems to confirm that neither Philip Mount or the magazine chose the items for this “super system”. It also shows that the reviewer seems to take for granted that only bigger, most costly, speakers would do – i.e. pre-judgment being relative price! Although the review largely lacks relevant measurements the reviewer did then give a brief description of the 602 speakers:

“These units are new from Armstrong and represent their first commercial loudspeaker. Drive units chosen are a mixture from Isophon, Audax and Peerless, I believe, the 20·3cm (8-inch) midrange driver being loaded by reflex enclosure with resistive port, a principle explored most notable and successfully by Celef. Construction and finish of the 602s was very good, the review samples being supplied in a light but distinctively grained teak veneer that had been extended to cover the front panel so that they may be used with black filter-foam grilles on or off.”

He then went on to give his ‘subjective’ personal opinions:

“Sound quality produced by the 602s is probably more a reflection of what their designers consider to be most desirable for classical music, following what has become a rather common formula it seems to me where emphasis is placed on mid-band and treble performance, while the subject of low-frequency output has been more or less shoved under the carpet. I think Spendor were largely responsible for unwittingly promoting this approach to loudspeaker design by turning out units that achieved enormous approval for their exceptional midrange and treble qualities while being pretty average at low frequencies.”

Which made plain that he wasn’t a fan of such speakers, despite them proving very popular and successful with users at the BBC, etc. On that basis he went on to say:

“In their favour I feel the 602s produce a fairly well integrated and smooth sound over most of the audio band, with very slightly falling treble output (subjectively). There is an obvious colouration that takes the form of a wooden thrum or boom that I don't like and is obviously contributed by the cabinet.”

before concluding that:

“Percussive instruments. particularly drums really didn't come over at all and so with regard to modern rock music I would count the 602s out. They're quite pleasant with certain types of light classical music though and weaknesses intrude little. This includes opera. I feel however that a really good loudspeaker should handle the widely differing demands of all forms of music with equal competence, a goal the 602s consummately fail to achieve.”

It is hard to disagree with the ideal that a good loudspeaker should handle all forms of music. But, that given, we can ‘review this review’ by posing a simple question...

Imagine if the system had been changed by replacing the 602 speakers with, say, QUAD Electrostatics. What would we think of a review that concluded they were not “really good loudspeakers” and ended using the words above?

Note that the review doesn’t simply say that the speakers might not suit some users. It requires any “really good loudspeaker” to handle all forms of music with “equal competence”. In effect, it considers that “not good for everything” meant the same as “good for nothing”. Yet in reality all loudspeakers are compromises of one kind or another. The Electrostatics were around £450 a pair at the time. More in line with the percentage of the total system cost the reviewer assumed to be required. This made them far more costly than the 602 speakers – yet they might have been even less suitable for “modern rock” music. Despite this, they had, and still have, many very happy users who’d argue they are “really good speakers”. And you could make similar points about speakers made by Spendor, KEF, and others which adopted the same “BBC” approach to speaker sound. With all this in mind we can also remind ourselves that Angus McKenzie’s published comments indicated that he was rather more balanced in his views on the 602s.

The difficulty this points to with ‘subjective’ reviews is the extent to which they may draw sweeping conclusions based on the prejudices, preferences, and circumstances of the individual reviewer. But which many readers might not share, or even know, and so may not agree with the reviewer’s conclusions. It’s all too easy for a review to tell you what the reviewer likes and dislikes, not what the reader will actually like or dislike. To make this worse, there are also problems with the choice of a ‘system’ when a review is to produce ‘subjective’ opinions without relevant supporting measurements.

There is a basic problem here with the way items in a ‘system’ may interact. Here I can illuminate this by asking another simple question about the Practical Hi-Fi review: How can we tell that the (alleged!) bass problems the reviewer reported were actually due to the speakers, and were caused by the cabinet as he believed? Loudspeaker assessment is notoriously fraught with pitfalls. This question can in turn be illuminated by asking a different question: What if the reviewed system had included, say, a different amplifier? Given the possibility of the sound being changed due to impedance interaction between amplifier and speaker, this might produce a change in the audible results. As might carrying out the tests in a different room!

In fact, the 602 was developed and designed with the aim of providing speakers that worked well with the 600 range amplifiers. And – as previous reviews of the 600 range show – the range’s amplifier had unusual behaviour in the way its output impedance varied with frequency. Because of this, the 602 might have sounded noticeably different if the ‘system’ review had used an Armstrong amplifier. Of course, it would be fair enough for a reviewer to argue that the speakers should usually work well with other well-designed amplifiers. (And for all we know from the review, the 602s did!) However given this issue was well known by engineers, it would seem reasonable for it to be pointed out in a review to avoid misleading some readers.

Omitting this seems particularly odd given that the reviewer himself made evident that he thought the 602 was a strange choice for the system being reviewed. If the review had included relevant measurements on the amplifier, etc, knowledgeable readers could have made their own assessment of such possibilities. Alas, a largely ‘subjective’ review of this kind doesn’t bother to give the relevant evidence. It just tells the readers what to think.

The above is (currently) the last Armstrong 600 series review I am aware of. In some ways it was a sign of what was to come. But, from this point on, the most important developments were inside Armstrong. I’ll deal with those on another webpage and explain the events which led to Armstrong ceasing to be active as a manufacturer in the early 1980s...

Jim Lesurf

6700 Words

22nd Nov 2015